The Librarian's Late Return

Dr. Frank Wesbrook was faced with many competing priorities on being hired as UBC’s first president, but one of the most pressing was the establishment of an adequate central library.

For advice, he turned to a former colleague from the University of Minnesota, the institution from which he had recently been recruited. James Thayer Gerould was librarian there. He agreed to help stock UBC’s Library in time for the university’s opening in 1915.

“My dear Doctor Wesbrook,” he wrote in a letter dated March 14, 1914. “At your suggestion, I am sending for your consideration a plan by which, at a minimum of cost, your University may have, when it opens its doors, a library adequate to its needs at the outset and which will be the nucleus of a later and greater collection.”

The plan involved travelling to Europe, where Gerould believed he would be able to secure a better price – as much as 20‑30 per cent less – by going directly to dealers and bargaining on the spot.

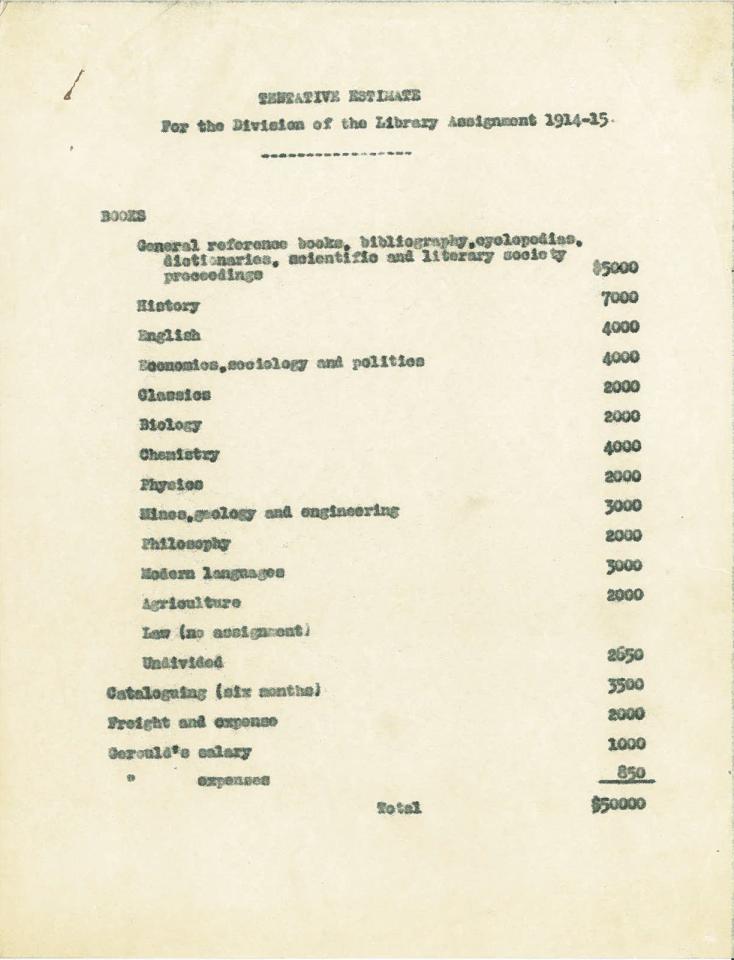

“My suggestion is, therefore... that you appropriate the sum of $50,000 for the immediate purchase of books for your library and that I be given a commission as your agent to visit England, France and Germany to buy the books.”

Since Wesbrook had yet to hire a librarian, Gerould also offered to oversee classification and cataloguing. He asked for a salary of $250 per month plus travelling expenses and requested a swift decision, because he thought it best to leave as soon as possible.

By the following month, an agreement was in place. The librarian set sail from Boston on May 5 on the S. S. Cymric of the White Star Line. “I am eager to get at the job and to make good on your gamble,” he wrote to Wesbrook the day before.

Later that month another letter arrived in Vancouver, written on notepaper from the Imperial Hotel in London’s Russell Square. Gerould reported that he had secured the services of export booksellers Messrs. Edw. G. Allen and Son, Ltd. Allen was one of only two sellers Gerould trusted to do the job, which was to include binding or rebinding books before they were shipped, via Blue Funnel Line, on a 72‑day journey across the Pacific. Gerould and Wesbrook had initially discussed shipping the books in in tin‑lined cases, but instead – because it weighed less and was cheaper – Gerould recommended using heavy waterproof paper.

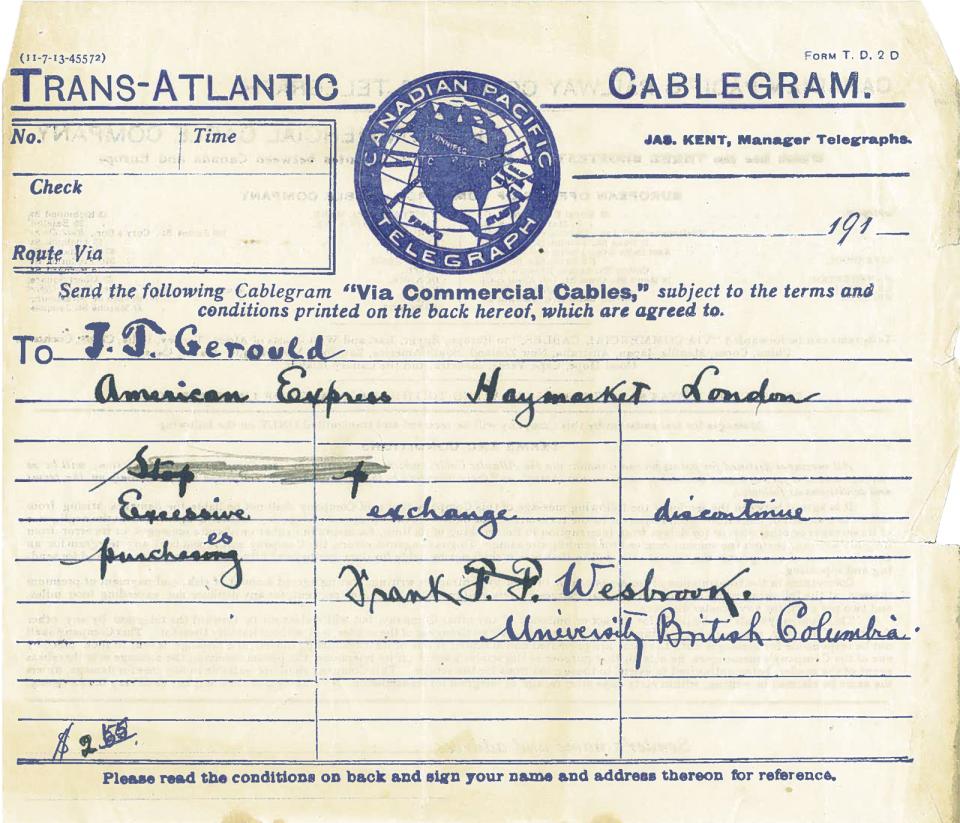

For the next few weeks, Gerould went about his business. A letter from Wesbrook dated June 16 indicates that they had inadvertently overlooked a subject: “It is strange that we missed mathematics,” he wrote, instructing Gerould to cut $1,500 proportionately from other subject areas and put it towards math books. Another time, a cable arrived asking Gerould to discontinue purchasing because of excessive exchange rates.

In July, after making large purchases in Oxford and Cambridge, Gerould made his way to Paris. After that, the plan was to go to Leipzig in Germany.

He found conditions in France less favourable. “I am not so well satisfied with what I have done here as I was in England,” he admitted to Wesbrook towards the end of his stay there, “but... I don’t suppose I can hold myself responsible for the disorderly condition of the Paris book trade.”

He found most books unbound and stock to be poorly classified. It also rained a lot and he worked long hours. “I shall be glad to get out of it myself for the twelve and fourteen hours work which I am doing here is beginning to tell on me,” he confided.

Although Gerould was eager to leave Paris, he would find things far more disagreeable in Leipzig. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand had occurred a few days earlier, and war in Europe was imminent. In a letter to Wesbrook dated July 31, three days before Germany declared war on France, Gerould documented the situation in Paris.

“On the surface, perhaps the most striking thing is the scarcity of money,” he wrote. “A week ago one almost always received gold in exchange for a note of the Bank of France but on Monday of this week it all disappeared...”

He observed that the streets were crowded yet orderly, with a strong police presence. But chaos would not be held in check for long. A trial involving a Madame Caillaux was underway in France at the time. She was the wife of politician Joseph Caillaux and had shot dead the editor of Le Figaro newspaper, which had been publishing letters her husband was writing to another woman as part of a media campaign against him by political enemies. It was judged a crime of passion and she was acquitted. When the verdict was announced, the Paris streets erupted.

“In the tensity of the moment it was enough to furnish the spark,” described Gerould. “In a few moments, bands of largely young men were parading up and down chanting almost in the manner of an American university yell. As‑sas‑in, Cail‑laux, Assassin Caillaux, Assassin Caillaux. Then the police would charge, drive the bands down the boulevard for some distance and then turning would drive the following crowd back again.” Gerould took refuge in a café. Things calmed down before long: “The man who swallows fire was performing before the terrace of the café, the postcard seller and the rag man had reappeared and it was as usual.”

Gerould still had a job to do. Would it be safe to go to Germany? “All sorts of advice has been given me but yesterday I wired my correspondent in Leipzig and as he advised me to come I am going to take a chance,” he informed Wesbrook. “The books are there and I hope that mobilization if it comes will leave someone with whom I can do business. In any event I can only do my damnedest.”

The letter was likely delayed by wartime conditions, and Wesbrook would not receive it for a few weeks. Days went by with no word from Gerould.

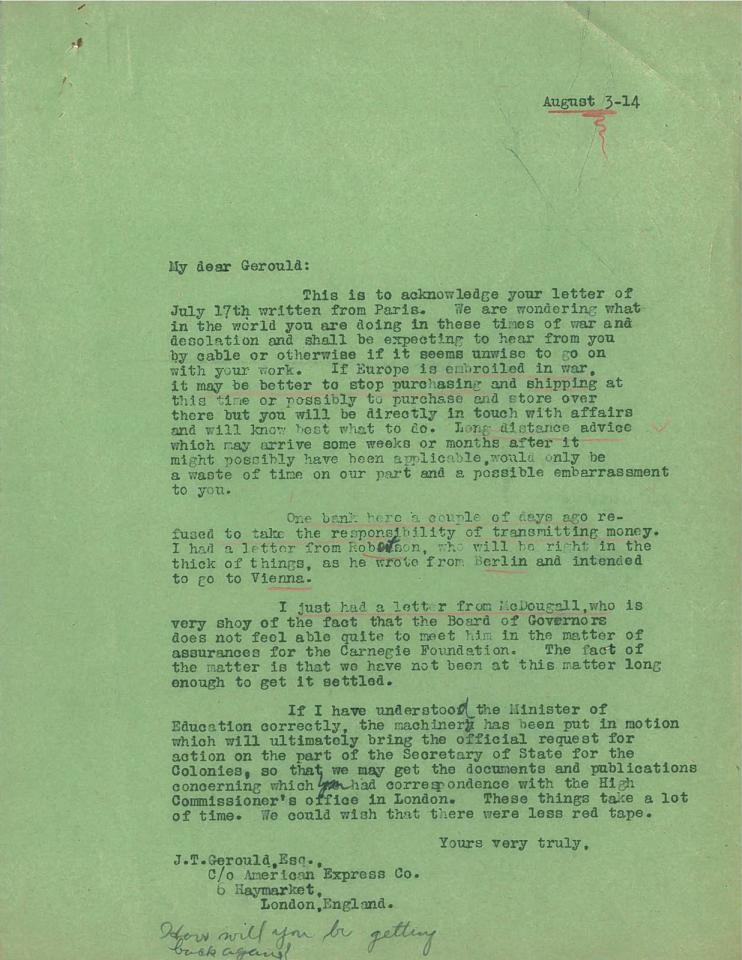

“We are wondering what in the world you are doing in these times of war and desolation and shall be expecting to hear from you by cable or otherwise if it seems unwise to go on with your work,” the university president wrote to him on August 3. “If Europe is embroiled in war, it may be better to stop purchasing and shipping at this time...” And on the bottom of the typed letter, scribbled in pencil: How will you be getting back again?

On August 8, another letter from Wesbrook expressed anxiety about the fate of the books:

“I have been wondering whether they are covered by insurance which would protect us against loss in case of seizure by Germany. These are things however, which perhaps we cannot help at this time.”

By August 11, his anxiety was about the fate of Gerould:

“I was not at all disturbed about you until now. I do hope that everything has gone all right with you. We have not received an answer to the cable sent the other day...”

Then a letter arrived that could only have added to the president’s unease. It was from Miss S. L. Stewart, Gerould’s secretary.

“Here at the University of Minnesota we are considerably exercised about the where‑abouts of Mr. Gerould,” she wrote. “... It is only in the hope that you may have a little more definite information about him that I am troubling you. If you can let us know where he is, I shall be much obliged to you.”

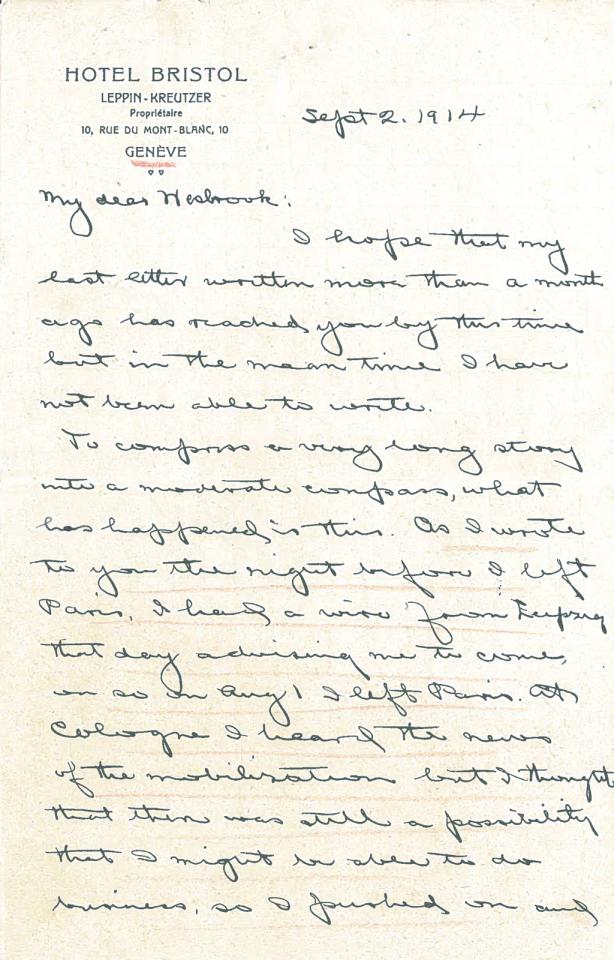

Meanwhile, as concern mounted among his friends and colleagues back home, Gerould had fallen into a predicament that caused his regular stream of letters and cables to be abruptly cut off. Although he wrote to Wesbrook as soon as he was able, on September 2, with a detailed account of what had happened to him, the president would not receive that letter, nor any other news about the librarian’s whereabouts and well‑being, until much later that month.

Gerould had arrived in Leipzig in the small hours of August 3. Later that morning he telephoned his correspondent, who now advised him to leave Germany as quickly as possible. Gerould boarded the last scheduled train for Basel, Switzerland, but the train was stopped at Mannheim and passengers were instructed to take a ferry across the river to catch another train at Ludwigshafen. The crowds were so great that Gerould failed to catch the train and had to find lodging for the night. The next day he stayed in his room. On August 5, he continued on his journey towards Basel. He was delayed by police for four hours at Landau, then allowed to carry on. But not for long.

“About three stations further on I was arrested and taken to the jail at Kandel* where I was examined, my luggage mauled, and I was stripped in the hope of discovering that I was an English spy. I had, of course, a good many business papers with me and letters from dealers in London and Paris. Most damnable of all I had the cabin plan of the Cymric and the groundplan of the Univ. of BC. Fortunately there was in town a grocer who had for a number of years lived in the States and he was able to go through my papers and pronounce them ‘alles harmlos.’”

The librarian spent the night in a cell and the next morning appeared before some judges: “... though when they left they assured me that I could not be released for two or three days,” he wrote, “ I was in point of fact freed at about two o’clock and committed to the care of the former American Mr. Stripf. He kept me at his house for three weeks and was very kind.”

Gerould had little cash. He was aided by the American Consul in Mannheim and friends in Leipzig, eventually making his way to Vevey, Switzerland. With the embassy advising against Americans coming to Paris, he would need to find another route home.

“I am in rather poor shape physically,” he told Wesbrook in his September 2 letter, “but it looks now as if I should have time enough to recuperate but I assure you that even Switzerland is far from being a good place to be at the moment.” The rest of Gerould’s letter dealt with the comparatively mundane business of book‑buying and the outstanding transactions from Paris.

Eventually, on September 17, Geroud was able to secure a route out of Europe, via Genoa, on a ship that was “large and comfortable, tho dirty.” A few days before the sailing, he sent Wesbrook a letter from Le Grand Hotel in Nervi, eight miles from Genoa. “It is a lovely place overlooking the Mediterranean and I spend most of the day sitting under palm trees… It is rather hot in the middle of the day but the nights are cool and it is altogether delightful. The hotel is one of the best on the Italian Riviera...”

By this time, Wesbrook had finally learned, via a third party, that Gerould was safe and on his way back to the States – but he had yet to receive the librarian’s letter containing the details of his encounter with the German authorities.

“My dear Gerould,” he wrote on hearing the good news, “I have not the least idea how many letters and cables of mine reached you, but we have been very much exercised about you... The first consignment of thirteen cases of books arrived and I received the notice yesterday and ordered the cases taken to the storage warehouse... I shall be glad to see you sometime in the near future and to hear your adventures. As I wrote to Miss Stewart, I hope they will have been interesting, but not too interesting.”

* Please note that Gerould’s handwritten letters are difficult to decipher in parts. The place names described above are, in our best judgment, correct.

Thanks to UBC Archives for providing access to correspondence between Wesbrook and Gerould.

University Librarian receives honorary fellow award

UBC’s University Librarian, Ingrid Parent, has this year been conferred an Honorary Fellowship by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). Parent is the third Canadian to be given this distinction; 30 fellows have been honoured since 1936. The honour is the association’s highest award and conferred on the basis of merit.

An active member of IFLA since 1995, Parent served as its first Canadian president from 2011 – 2013. She has been noted for engagement in promoting Canadian libraries in the international library community. Her presidential theme, “Libraries a Force for Change”, highlighted the global digital potential of libraries to provide inclusive and transformative services, innovative ideas, and new ways to collaborate. Her other achievements with IFLA include the development and release of the IFLA Trend Report, which has been published in over a dozen languages. The Report encourages library communities to lead, shape, and drive the evolving digital information environment.

“The quality of an international leader is always expressed in their ability to remain engaged in the issues of concern to their home constituency,” says Sandra Singh, President of the Canadian Library Association and Chief Librarian for the Vancouver Public Library. “In this way, Ingrid truly demonstrates her dedication to library priorities and professionals, not only on the world stage, but also within Canada.”

In her role as University Librarian, Parent has used her international experience to bring the world to the UBC campus. In 2012, UBC Library hosted the Indigenous Knowledges conference and was instrumental in bringing the UNESCO Conference, The Memory of the World in the Digital Age – Digitization and Preservation, to downtown Vancouver. In 2013, the Library hosted the annual meeting of the Pacific Rim Digital Library Alliance, which drew scholars from both sides of the Pacific and, the University has benefited from a number of national and international partnerships including those with Peking University Library and the University of Washington’s Library. Parent is a UBC alumna, graduating with a BA Honours in History and Library Science degree, and has a honorary doctorate from the University of Ottawa.

The award was presented to Parent in Cape Town, South Africa in August during IFLA’s World Library and Information Congress.