Portrait of the Artist as an Old Woman

In which Hinda Avery, PhD’93, makes a case for elderhood, activism, and comics, just by being herself.

Hinda Avery disturbs the peace. She doesn’t mean to. “The last thing I’m trying to do,” she says, “is offend anyone or be insensitive.” She speaks sincerely, so it might be less a result of what she does than simply who she is: a single, never‑married‑by‑choice, happily child‑free, vocal, 79‑year‑old radical second‑wave feminist activist, educator and philosopher, animal welfare activist and student, fine artist, comic book artist and filmmaker, second‑generation Holocaust survivor and Nazism resister. Oh, and she’s funny. It’s a devastating combination.

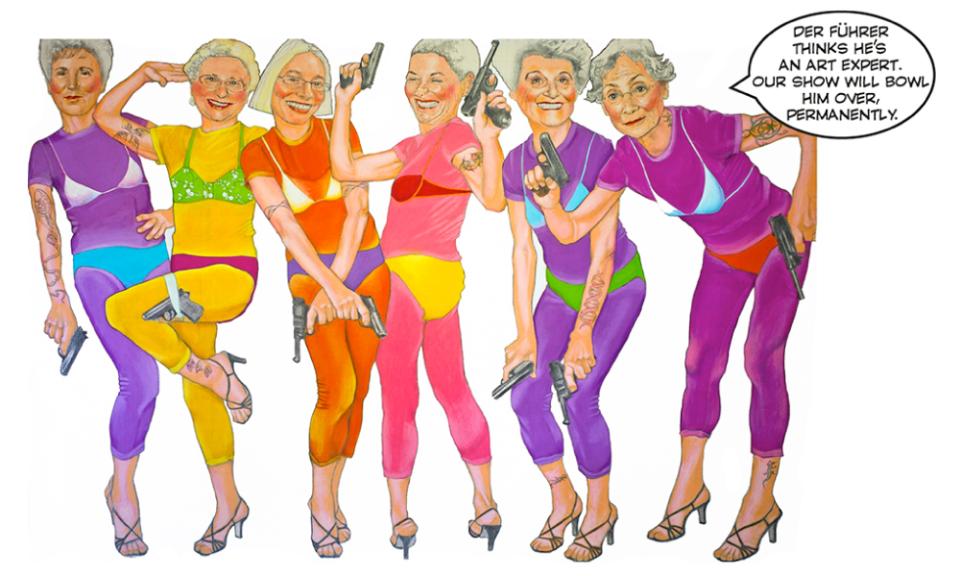

She doesn’t look like a troublemaker. Diminutive, simply dressed, grey‑haired and smiling, she is the very picture of retired respectability. Which can make the F‑bombs a bit of a shocker. In 2005, after decades in academia, Avery launched a second career as an artist, initially as a way of comprehending her family history. She painted the women in her mother’s immediate family who’d been murdered in the Nazi Holocaust of WWII, adding in her mother, her sister, and herself. Over time, no longer wanting to see herself and her family as victims, she began to paint larger figures in colours less typical of concentration camps than of the comics she’d loved as a child. She gave the women voices – and guns. She called them warriors and wonder women. She named them the Rosen Resisterrrz, after her mother’s family. Eventually, she added Der Führer himself, and made him the victim – of her paintbrush. “I really like the idea of working with a different view of the Holocaust,” she says, “and using laughter and confidence as a weapon.” Come to think of it, maybe it is what she does that gets some folks riled up.

Not everyone was a fan. “Many members of the Jewish community... didn’t see this as something funny, didn’t see [Hitler] as a cartoon character,” Avery says. “They felt this was too sensitive of a subject and that I shouldn’t be tackling him the way I did.” Nevertheless, the Resisterrrz appeared in galleries around the city, and Vancouver Courier editor Michael Kissinger made a film about her work called Hinda and Her Sisterrrz. “Smiling, foul‑mouthed, bikini‑clad elderly women holding guns?” Kissinger says. “I was sold.” It became an official selection of the 2017 Jewish Film Festivals in Toronto, San Francisco, Boston, Vancouver, and Victoria.

Andrea Van Noord, a University of Victoria Germanic and Slavic Studies professor who has used Avery’s artwork in her classes, says, “Typically when you talk about Holocaust representation you [see a] natural progression [over three generations] of taking more risks, being more confrontational, more creative in how [artists] choose to talk about it. With Hinda, you see … three generations of thinking within a single body of work. It’s extraordinary.”

Avery exhibits an instinctive intelligence in both her changing approach to her subject matter and her use of humour as a form of resistance. Although she has some regrets about choosing teaching over a career in art earlier in her life, her power as an artist now is fired by her evolution as a woman, a feminist, a philosopher, and a second‑generation survivor. In other words, this art could only have emerged at this time. And given the recent rise of neo‑Nazism, Avery’s timing is impeccable.

In Why Civil Resistance Works, Drs. Stephan and Erica Chenoweth write that in over 320 conflicts between 1900 and 2006, nonviolent resistance was more than twice as effective as violent resistance in achieving change, and that humour is a particularly powerful tool. In 2014, the German town of Wunsiedel turned the annual neo‑Nazi pilgrimage to Rudolf Hess’ gravesite into “Germany’s most involuntary walkathon.” For every metre the neo‑Nazis marched, locals pledged 10 euros. A sign at the “finish line” thanked marchers for their contribution to the anti‑Nazi cause – close to $12,000 USD – amidst showers of rainbow confetti.

Personally, the Rosen Resisterrrz led Avery to some measure of healing. Artistically, they led her to comic books. She created Bayla’s Issues, a series of underground comics about an older Jewish woman who wants to be a world‑famous artist but struggles with inner demons, a lack of confidence, and the ravages of age. “She’s an anti‑heroine,” Avery says. “It’s been the opportunity to express darkness. There’s no happy ending.” The switch from fine art to cartoons, though seemingly regressive, is in fact the action of a revolutionary. In their capacity to foment change, and with a global market share in the billions of readers and dollars, comics, manga, and graphic novels are the tools of our time.

The switch from fine art to cartoons, though seemingly regressive, is in fact the action of a revolutionary. In their capacity to foment change, and with a global market share in the billions of readers and dollars, comics, manga, and graphic novels are the tools of our time.

Avery names Daniel Clowes and Robert Crumb as underground favourites. “They’re about one’s inner lives,” she says, speaking of their comics or perhaps of her own, “and our struggles between our values and principles and our dark desires and temptations. How much harm are we allowed?”

Avery has turned the basement of her early‑1900s wood‑frame house into a simple studio, and works in the mornings with CBC Radio 2 for company. She chooses a topic and a layout, then begins to sketch. Graphic artist Tony Bosley, the son of a close friend, scans the sketches and drops in the colour. “I have a terrible time with the text,” Avery says. “When I come up with the right punch line, it does give me a chuckle. [But] there’s a lot of pain in the jokes.”

This time around, Avery is ready for the controversy. “Bayla’s an older woman with wrinkles,” she points out. “We’re not used to seeing images of women with wrinkles. And the swear words. And they’re not positive.” But the underground scene has been a welcoming space for women writers and artists, so although the hyper‑sexualization of young female characters is still predominant in comic book imagery, the tide is turning.

“I’m obsessed with the portrayal of women in the media,” Avery says, “which I think is really very demeaning.” She has just seen Woman at War, an Icelandic film starring Halldóra Geirharòsdóttir as Halla, a 50‑something choir director living a secret double life as an eco‑activist. “It’s a portrayal of a woman one would never see coming out of Hollywood,” she says. “It blew me away.”

Avery has produced and directed two films herself, starred in a third, and is working now with Michael Kissinger to turn Bayla into an animated short. Kissinger sees Bayla as a kind of Charlie Brown figure, “if Charlie Brown was an elderly Jewish woman.”

“I’ll be glad if it happens in my lifetime!” Avery says, laughing. These are the jokes when you’re 79.

“I’m obsessed with the portrayal of women in the media, which I think is really very demeaning.”

Unlike Halla, Avery has never made a secret of her politics or her passions. “I discovered the women’s movement in the late 60s,” she recalls. “I was a hippie. I remember reading Betty Friedan’s book [The Feminine Mystique] and just...” She uses her hands and arms to depict a descending cascade of awareness. She recalls the spirit of feminism’s second wave: “That feeling of finally, finally we could be who we wanted... of breaking out of the chains. In those days, we thought the changes would be vast and permanent.” Avery marched after Trump’s election, and follows third‑ and fourth‑wave feminist movements such as #metoo and #timesup. “I have remained militant all these years,” she says. But she worries about women burning out. “These issues we were tackling in the 60s and 70s we’re still tackling today.”

Ironically, one of feminism’s biggest challenges today is infighting: mainstream or liberal feminists pitted against radicals, celebrity icons and front‑liners duking it out for media real estate, and younger feminists jockeying for power and visibility against older women who want to stay relevant in the movement they’ve dedicated their lives to. Unless and until all feminist voices are heard, the only winner is the patriarchal status quo.

Avery was one of Vancouver’s first teachers of women’s studies. “It was a new discipline in those days,” she says. “It was an awakening. I recall several women [students] changing their lifestyles.” She also lectured on women’s issues in architecture and urban planning, the subject of her PhD dissertation, and produced an award‑winning education program called “Environments for Girls and Women: City Design from a Feminist Perspective.” She says now, “I wanted – and want – a much more gender‑neutral place to be.” The World Economic Forum’s annual Global Gender Gap Report along with Price Waterhouse Cooper’s Women in Work Index pinpoint the best places in the world to be a woman. Iceland is one. The country starts gender equality lessons in preschool, protects women’s equality in work with legislation, outlaws gender discrimination in advertising, schoolbooks, and the workplace, mandates gender equity in corporations and on boards, has made the profiting from sexual exploitation illegal, has a Ministry of Gender Equality in its government, and offers the best parental leave policy in the world. As of 2018, Canada ranked 16th on the list, and the US 51st.

She recalls the spirit of feminism’s second wave: “That feeling of finally, finally we could be who we wanted... of breaking out of the chains. In those days, we thought the changes would be vast and permanent.”

Avery’s Rosen Resisterrrz canvases are rolled and stored in plastic sleeves in her studio, and her new animation is in Michael Kissinger’s hands for now. What is next? “I don’t know,” she says. “I’m kind of lost.” Avery has just completed a fourth‑year course in UBC’s world‑renowned animal welfare program entitled, “Animal Welfare and the Ethics of Laboratory Animal Use.” The course looks at public concern for animal suffering, debate about the benefits of the research, concern over the genetic modification of animals, and the capacity of animals to sense and express pain. “It’s been traumatic,” Avery admits. “I feel like I’m sitting in a Holocaust Studies course. I think my history is the reason I’m involved in animal rights and animal advocacy.” A trustee of the BC Foundation for Non‑Animal Research, Avery is not the first to draw comparisons between the treatment of Jews by Nazis during the Holocaust and the daily treatment of factory farm and research animals worldwide. It’s a controversial stance that the Anti‑Defamation League (ADL) and others have criticized as anti‑Semitic. But proponents say the parallels are less about the victims than the perpetrators, and the arbitrary distinctions that allow us to value certain lives over others. Parallels or no, when 95 per cent of the drugs tested on animals now fail in human clinical trials, we have to ask: How much harm, indeed?

These days, Avery feels keenly the limitations on her time and her energy. She could choose dotage over conscious elderhood. Peace over continued political action. Except that such choices would require her to be someone other than who she has become. Audre Lorde (1934‑1992), an American feminist and civil rights activist and a contemporary of Avery’s, said, “I am not free when any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.” It’s a good bet that until everyone has a measure of peace – humans, animals, and Earth alike – Hinda Avery will keep on disturbing ours.