How mRNA technology could transform how we treat disease

B.C. could be the next hub for developing and manufacturing the high-tech vaccine platform.

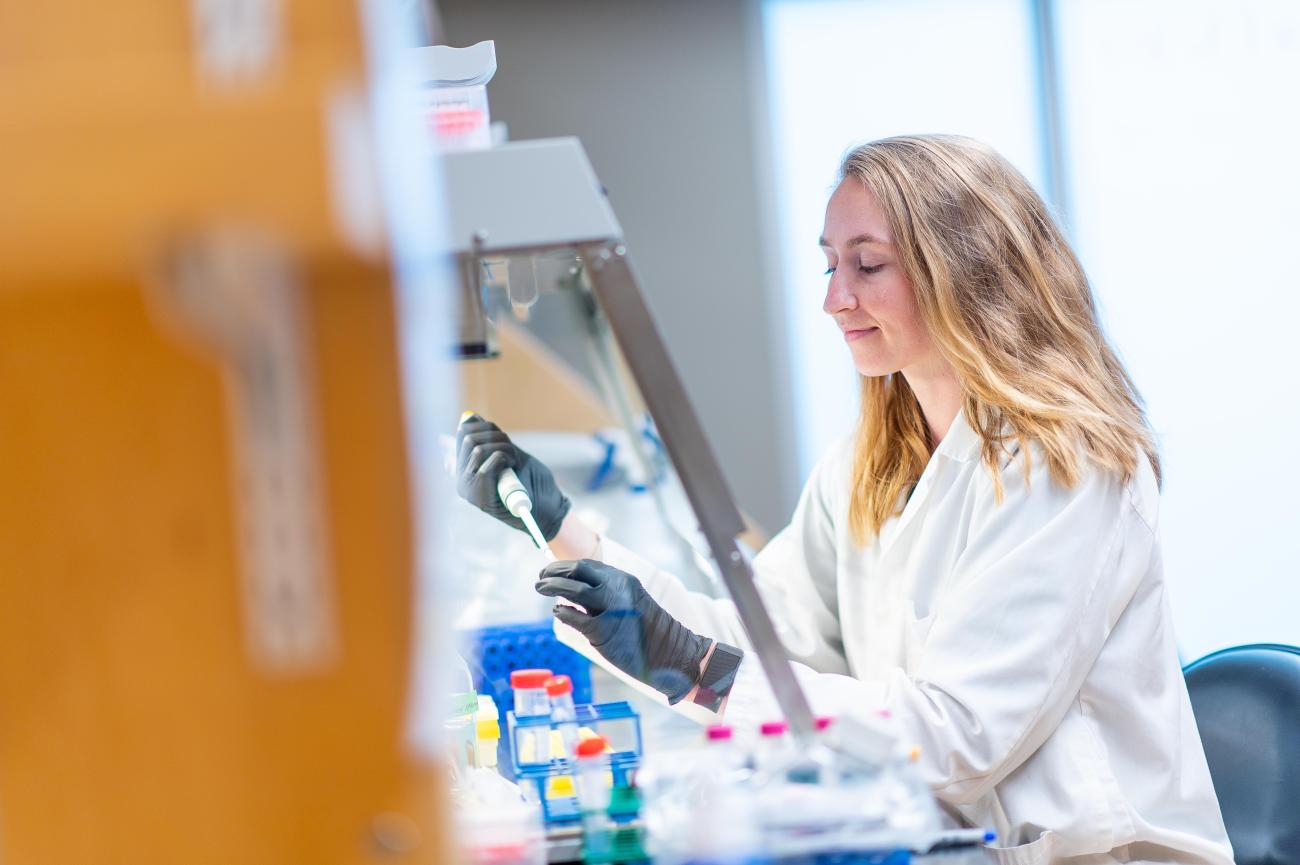

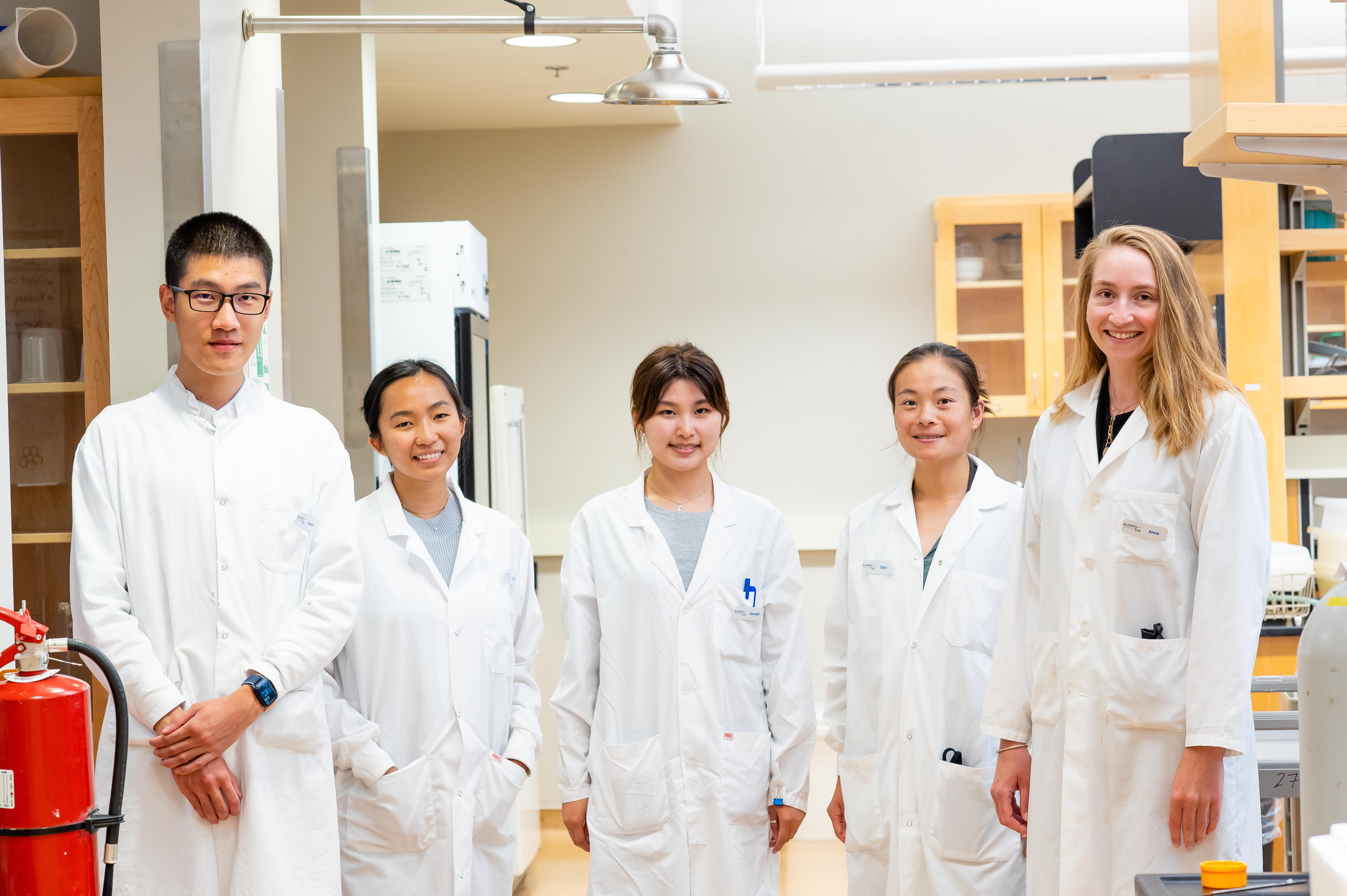

When Dr. Anna Blakney interviewed for a position at the University of British Columbia at the start of 2020, mRNA technology — her area of research expertise — wasn’t yet widely known by the general public.

Then COVID-19 hit. Today, more than a billion doses of mRNA vaccines have been administered worldwide to protect against the novel coronavirus.

For Dr. Blakney, now an assistant professor at UBC’s Michael Smith Laboratories and school of biomedical engineering, seeing how rapidly a safe and effective mRNA vaccine could be developed, tested, manufactured, and administered has been incredible.

“Before the pandemic, nobody had ever done a Phase 3 trial with an mRNA vaccine before,” says Dr. Blakney, who was part of the team at Imperial College London that developed an mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 before coming to UBC. “They have such a high safety profile and such high efficacy, and I don’t think anybody really was even expecting that.”

With the end of the pandemic finally in sight, scientists are now turning their attention to the future of mRNA technology. Many experts, including Dr. Blakney, believe the platform has the potential to transform how we treat and prevent a wide range of diseases in the future.

There’s also strong potential for UBC and British Columbia to become the next global biotech hub for the development, testing, and manufacturing of these types of cutting-edge vaccines and therapeutics in Canada and the world.

Already, Metro Vancouver is becoming increasingly known for being home to a flourishing biotech sector through the successes of UBC spin-off companies such as Acuitas Therapeutics, which contributed to the lipid formulations needed for the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine to enter human cells; Precision Nanosystems; and AbCellera. AbCellera, which has developed innovative COVID-19 antibody therapies, is also currently building a 130,000-square-foot facility in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood that will expand its capabilities in bringing new antibody therapies to clinical trials.

“UBC is a vibrant hub in leading the development of the biotech industry in B.C.,” says UBC’s Vice-President, Health, Dr. Dermot Kelleher. “There is immense potential to continue building our biotech industry, which will have a profound impact on the health and wellbeing of British Columbians, and could better equip the province, and the country, to be able to respond to the next pandemic.”

A potential future treatment for cancer

Before the pandemic, BioNTech, the company that partnered with Pfizer to make that vaccine, was in the process of developing a cancer vaccine, but it was still years away from market. Today, the company is recruiting for Phase 2 of a cancer vaccine to treat patients with advanced melanoma.

While it may seem unusual that a vaccine for COVID-19 could also be used to treat cancer, Dr. Blakney says it demonstrates the wide-ranging potential of the mRNA platform. With COVID-19 serving as “proof of concept” for mRNA vaccines to get off the ground quickly, she says the potential for future applications is significant.

“The plane is off the ground, so to speak,” says Dr. Blakney. “Although these are still first-generation vaccines, and there is still a lot of room for improvement, COVID-19 has just brought an incredible momentum to the field.”

At a basic level, mRNA vaccines work by training the immune system to recognize a pathogen that it has never seen before and to produce antibodies.

In the same way that the COVID-19 vaccine trains the immune system to make antibodies to protect against the spike protein found on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, a vaccine can also be developed to recognize a protein on the surface of a cancer cell.

“Cancer cells often have unique proteins on the surface that are specific to them,” Dr. Blakney explains. “With mRNA vaccines, we can train the immune system to recognize that protein and kill it, thus treating the cancer.”

Improving existing vaccines for flu, yellow fever, and more

Another possibility for mRNA technology lies in improving the efficacy of existing vaccines like the flu shot, which Dr. Blakney says aren’t as effective as they could be.

Twice a year, global health experts review the results of ongoing global flu surveillance and make recommendations for the composition of flu vaccines.

As the majority of flu vaccines are still grown in chicken eggs, it takes many months for them to be developed and manufactured, during which time other influenza viruses can begin circulating. As a result, the flu vaccine is only about 30 to 40 per cent effective in a good year.

“But if we are able to make a flu vaccine synthetically — like we can with mRNA — it would significantly cut down the amount of time it takes to manufacture it,” Dr. Blakney says. “We could potentially monitor influenza viruses in real-time and release three or four strains of a much more effective vaccine over the course of one winter.”

Dr. Blakney adds that mRNA technology can also be used to improve the safety profile of vaccines like the one used to prevent yellow fever, a viral infection that occurs in Africa and South America. Although it is an incredibly effective vaccine, it can have serious side effects like possible organ damage.

Establishing BC as the next mRNA biotech hub

For Dr. Blakney, the beauty of the mRNA platform is that it doesn’t require a massive factory for manufacturing.

Contrary to traditional vaccines, which often require enormous bioreactors that take up a lot of space in order to grow cells, mRNA vaccines can be produced in a test tube. Their relatively small footprint makes mRNA vaccines the perfect technology to develop here in Metro Vancouver, where space is limited and land sells at a premium.

“Because it’s synthetic, you don’t need cells,” Dr. Blakney explains. “I could make a million doses of mRNA vaccine in a 100 mL test tube and the setup that would be needed could basically fit in my current lab.”

Combined with UBC’s strong innovation track record, Dr. Blakney says she believes B.C. could be poised to become the next big global biotech hub like San Francisco and Boston.

Further developing B.C.’s biotech system not only creates the potential for significant economic growth but it also supports job creation, which could help retain the strong talent that already exists at UBC, she adds.

“Vancouver is an amazing place to be working in biotech now,” she says. “That’s partly what drew me here — the potential to work in such a collaborative and interdisciplinary space. I hope that it continues to grow.”