Illustration by Asia Pietrzyk

Under pressure

Anxiety and depression are widespread among today’s students. Campuses are helping the vulnerable find healthy ways to cope.

Please note that this story contains references to suicide.

Olivia Lundman’s first year at UBC was a struggle. For the first time in her life, the kinesiology student was living on her own and felt overwhelmed by social anxiety. As a presidential scholar, she felt pressured to achieve top grades, and as a member of the Thunderbirds Track and Field team and Olympic hopeful, she felt compelled to improve her race walking times. “I would go to classes and then go to training,” says the self-confessed perfectionist.

On weekends, Lundman was a near-recluse, hunching over textbooks instead of socializing. She continually compared herself with others. “I felt I wasn’t doing as much and didn’t know as much as them,” she says, and observing her peers make friends and ease into university life only fed her sense of isolation and depression.

In her second year, Lundman made a concerted effort to socialize more, until the stress of midterms caused her to spiral again. “A mess,” Lundman called her mom, who urged her to connect with a physician and therapist. Following multiple counselling sessions, Lundman ended up “in a much better head space.”

Today, she is president of the UBC chapter of Jack.org, a charity that trains young leaders in advocating for mental health and revolutionizing care. “We mainly focus on awareness and education for mental health support,” explains Lundman. “We educate students on how to support others who might be struggling with their mental health, and we show them how to be there for themselves and how to be there for others.”

Mental health is as precious as physical health, but can be particularly precarious for students due to the Hydra heads of study pressures, holding down jobs to cover the high cost of rent and food, being away from family, and the more anti-social aspects of social media.

“Students at university are at the stage in their life where they’re experiencing huge changes as well as being placed under a lot of stress,” says Lundman. “And it’s also a stage when individuals want to impress their peers, which tends to cause them not to express their struggles to others for the fear of appearing weak.”

She also notes the effects of starting university during the pandemic. “I think a lot of students suffered academically and mentally because those social connections that you normally make in your first year were hampered.”

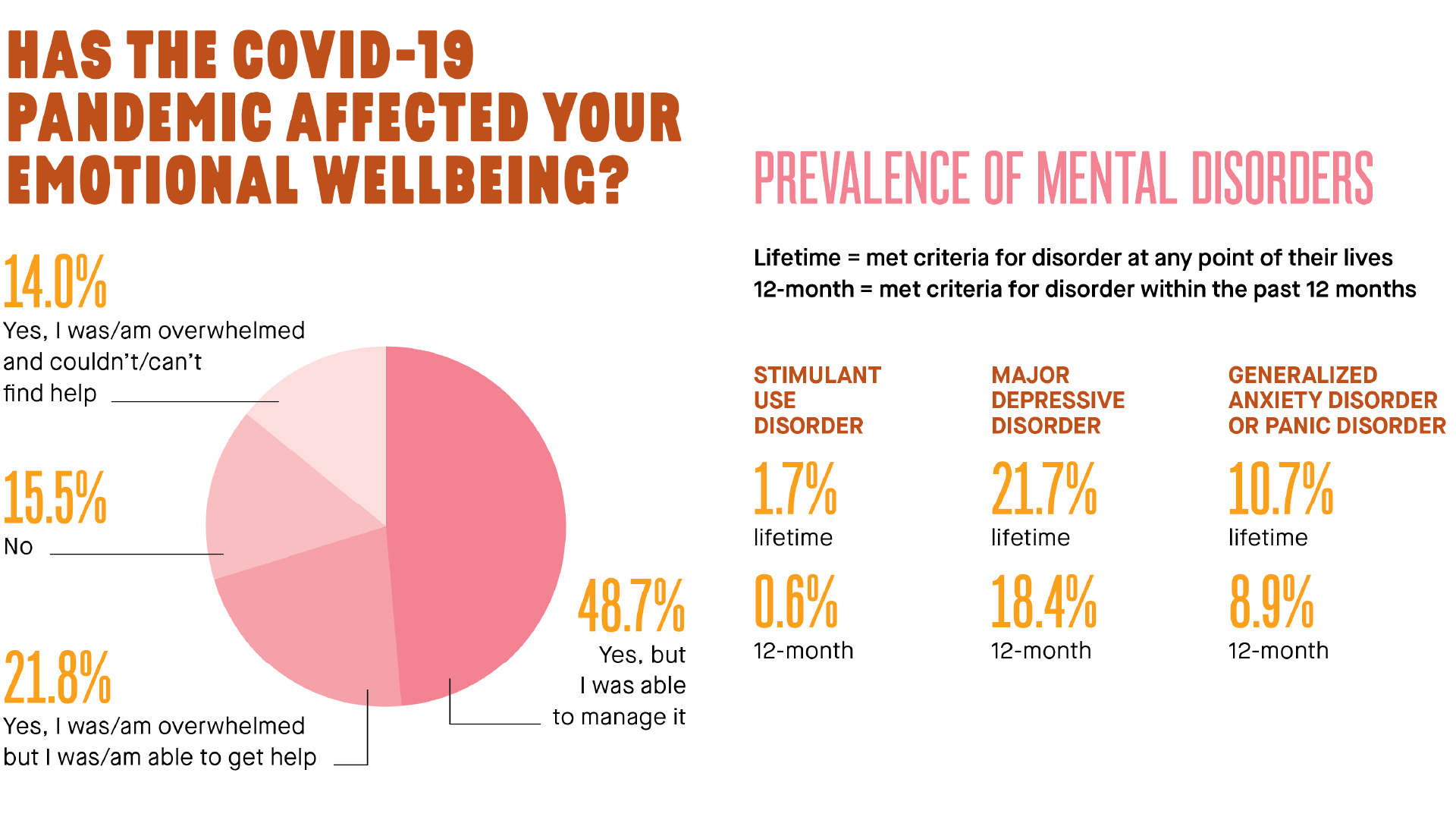

Dr. Daniel Vigo, an assistant professor in UBC’s Department of Psychiatry and School of Population and Public Health, says students are showing “widespread psychological distress and a high prevalence of mental disorders, particularly anxiety and depression.” This isn’t necessarily bad, says Vigo, as long as they remain below a certain threshold; sometimes, elevated stress, anxiety or sadness is expected, and, if managed adequately, can help students adapt to extreme circumstances like COVID-19. However, mental disorders can also become disabling, he adds.

(Story continues under graphic.)

Vigo, who is a psychiatrist and clinical psychologist, spearheaded the Student E-Mental Health Project, funded by Health Canada. Starting in 2019, just before the pandemic, a weekly online survey was sent to a randomized selection of students from UBC, the University of Toronto, McMaster, and SFU. Due to the timing, researchers had a “weekly photograph of how the mental health and substance use of students evolved during the pandemic,” Vigo says.

An important finding of the survey was how resilient students are. The majority coped well with COVID‑19. However, a “vulnerable” minority of about 14 per cent showed debilitating anxiety, distress, and suicidal thoughts, and were unable to access help. Some young people cope with stress by turning to alcohol or drugs, but others aren’t able to cope at all; Statistics Canada reports an average of 775 suicides every year among youth aged 15 to 29.

That statistic is partly why Lundman is so passionate about helping students who are struggling. “It makes me sad and angry that we’re losing all these lives due to our inability to address and advocate for everyone’s mental wellbeing,” she says. “There are so many different reasons why someone might make that choice, but I think there’s also a lot of things we can do to help reduce that statistic.”

Vigo’s research found that “suicidality,” which refers to thinking about, planning, or attempting suicide, seems to follow the academic calendar and is highest during final exams. His findings informed the development of an app called Minder, which was co-developed with UBC students and provides evidence-based interventions for psychological distress and substance use, including self-guided tools, connecting students with trained peer coaches, and immediately matching students mulling suicide with a counsellor at UBC.

Vigo estimates that nearly two per cent of UBC students meet criteria for stimulant use disorder in their lifetime, involving prescription stimulants, cocaine, methamphetamine or crystal meth. He is concerned about the availability of street drugs possibly contaminated with deadly synthetic opiates like fentanyl and carfentanil, and the risk these pose for accidental overdoses. The Minder app provides information on substance use while UBC’s Wellness Centre provides free fentanyl test strips as well as training in the use of naloxone, which reverses accidental overdoses.

On a more positive note, the survey found a majority of Gen Z is quite open to admitting mental health struggles. Lundman is a good example. Although she initially dismissed her angst as “normal school stress,” and pretended everything was fine, she eventually reached out to others who may have been facing similar anxieties by posting about her feelings on social media. On her Instagram page – “beneath.the.surface.x” – she shares her own mental health experiences alongside those of others she has encountered.

“My main goal is to increase awareness, because I think the more stories you read, the more de-stigmatized mental illness becomes, and the more you become accepting of those around you,” she says. “If we don’t talk about the pressure and the status of our mental health, then everyone’s going to just keep it all bottled up inside and continue to deteriorate on the inside.”

For UBC students needing help with day-to-day pressures, or those facing unexpected challenges, assistance is close at hand, with counsellors located at Brock Hall and embedded in faculties and programs across campus, says psychologist Dr. Kirby Huminuik, the director of Counselling Services at UBC. Students can book a remote or in-person session, often that same day, and they can get help to navigate the wide range of supports and services that are available. Mental health supports include self-directed resources, educational and interpersonal workshops, group therapy, individual counselling, and medical and psychiatric care. The counselling department has also launched an Indigenous Mental Health and Wellbeing initiative that supports Indigenous students in culturally appropriate ways.

Counselling, says Huminuik, helps students identify their strengths, sources of support, and inherent resilience, allowing them to navigate the pressures of school and life with confidence.

In addition, the extensive research undertaken by Vigo has provided a foundation for the Department of Psychiatry’s online resources, which he says will be available in the near future. And the effectiveness of the Minder app for decreasing psychological distress was recently proven through a randomized controlled trial including 1,500 UBC students. It is currently being adapted for implementation in various Canadian universities and across secondary schools in BC.

Now in her third year of studies, Lundman faces even more pressure this school term; she is prepping for an Olympic qualification race in April to determine if she makes the Canadian race walking team going to the Summer Olympics in Paris. She is grateful she sought counselling last term. “I was struggling with my mental health far longer than I was willing to admit. In the end, getting help enabled me to be happier and healthier, and allowed me to train at an even higher level than before.”

UBC students in need of mental health support can call 604 822 3811 or visit students.ubc.ca/health/counselling-services.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call Talk Suicide Canada at 1-833-456-4566 / Quebec: 1-866-277-3553 / Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868. If you’re in imminent danger call 911 or go to Emergency.