High Risk Zone: Diary of an aid worker in Sierra Leone

December 22, 2014

As I disembark from Lufthansa flight 492 at Vancouver International Airport, two young men in dark blue uniforms deliberately block the economy class exit; another pair blocks business class. Painful-looking telescoping batons hang from their hips as they check the passport of every travel-weary passenger. I saw this routine many times during my UBC Arts Co-op days when I worked with the Canada Border Services Agency, and I know exactly who they’re looking for: me.

I show my passport. The leader of the quartet tilts his head to his shoulder, radios to someone that I’ve been found, and leads me away. As we pass the airport’s mesmerising jellyfish aquarium, I ask if they really expected to find me in business class. “No, it was just in case you decided to wander.” They needn’t have worried; I wasn’t about to hide from the authorities: my carry-on is a big, fire-engine red duffel with “Médecins Sans Frontières” plastered on each end. “So,” he asks, “how was Sierra Leone, man?”

November 9, 2014

Following a two-day Ebola training course in Amsterdam, our MSF team flies to Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. As we walk off the tarmac at Lungi International Airport, a man directs us to a water-filled bucket with a simple plastic tap, on a stand to the left of the airport terminal entrance. He instructs us to wash our hands. During training we’ve been warned that, while hand-washing stations are omnipresent in West Africa, many are either empty or hold unchlorinated water. Curious, I raise my dripping-wet hands to my nose and inhale deeply. My head spins as not-so-fond memories of childhood swim lessons slap me in the face. I won’t repeat that mistake.

The immigration officer stamps my passport with a half-page visitor stamp reading “occupation in Sierra Leone prohibited” despite my multiple-entry work visa. As I watch his left hand pick his nose then return my passport, I’m already lifting a bottle of hand sanitizer from my pocket. Obsessive hygiene habits will regulate my every move in this Ebola-stricken country if I want to sleep soundly at night.

November 11, 2014

The Ebola management centre where I work in Kailahun, eastern Sierra Leone, is big. At peak occupancy, its 12 tents held over 100 patients. The Low Risk zone holds the on-site medical office, water and sanitation team area, laundry service, dispensary, change room, and dressing and undressing tents. The Public Health Agency of Canada’s mobile laboratory operates out of two canvas tents, also in Low Risk, testing samples every morning for Ebola RNA. The patients’ area – the High Risk zone – is straightforward: two tents for people suspected of having Ebola; two tents for people showing more symptoms than the suspect cases but not yet confirmed by the Canadian lab; and eight tents for patients testing positive.

As logistics manager for the MSF Kailahun Ebola management centre, I’m responsible for keeping the centre running smoothly. This involves construction and rehabilitation, infrastructure maintenance and repairs, site security, maintaining diesel generators, electrical systems and lighting, plus odd tasks such as setting up an outdoor projector screen and sound system to entertain patients with movies and dance music.

December 1, 2014

I’ve been called back to the centre – the lighting has failed in two of the patient tents. Without light, the medics are not allowed to work. Anna, a Dutch medical doctor specialising in infectious diseases, accompanies me. We enter the change room, swap regular clothes and footwear for hospital scrubs and rubber boots, and exit through another door into Low Risk. While I will be in High Risk, Anna will remain in Low Risk ready to manage any unforeseen situations.

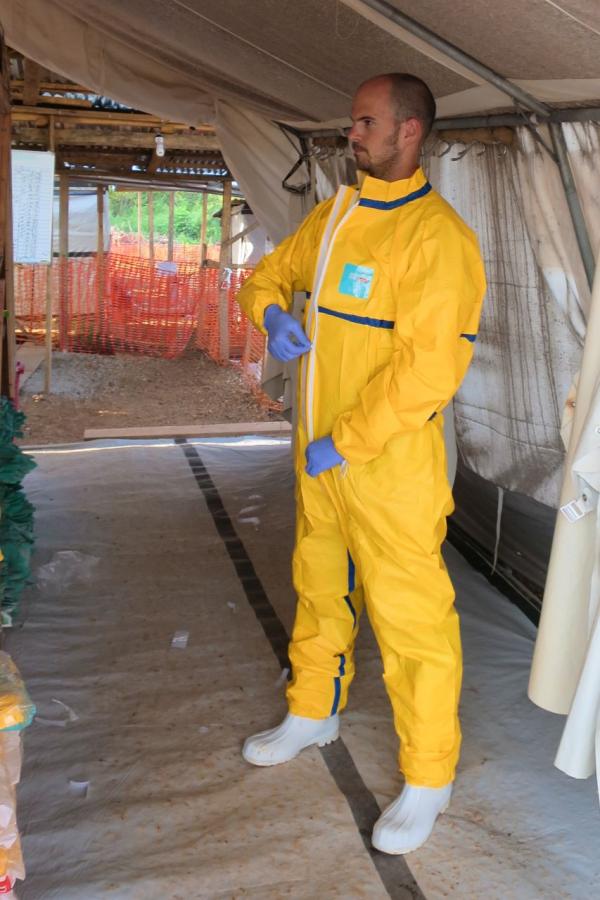

I can only enter High Risk with a buddy, so a hygienist named Foday comes too. If either of us leaves for any reason, the other will need to go too. In the dressing tent, we don our now-ubiquitous and colourful personal protective equipment (PPE), covering our faded turquoise hospital scrubs and white gumboots with a yellow spacesuit, white apron, blue nitrile gloves, pink facemask, white hood, anti-fog ski goggles, and green rubber gloves. Foday and I check each other for dressing mistakes – we’re responsible for each other's safety, especially any PPE “accidents” such as snagging and tearing the suit on an exposed nail or splinter, or exposing skin because of a goggles slip. Something as simple as fogged-up eyewear, or a facemask soaked with condensation, will trigger an immediate departure from High Risk. A fashion faux pas in an Ebola centre could be fatal.

Foday and I walk through the Suspect and Probable areas, and into Confirmed. Flashlights hang from strings tied to the tent frame; others rest against the faces of patients sleeping on canvas cots. Between two tents, we find two light garlands have been disconnected from each other. I reconnect them and the lights come on. Happy to have solved the problem, we begin telling Anna, still standing a safe distance away in Low Risk, when a light turns off behind her. A second later, the lights above us go out. I hit the nearby switch to turn the lights back on and hear a loud pop. Not a good sound. Then, I hear a much worse sound: the generator rumbling to a painful stop a hundred metres away. The remaining lights flicker out as the entire Ebola centre loses power.

“Oh no,” I think to myself. “What am I going to do now?” Still wearing full PPE, there’s no efficient way for me to get to the generator. I take two long, deep breaths, then send Anna with basic instructions for restarting the generator. This way, I can stay in full PPE a little longer and keep trying to get the lights back on in the two tents. However, five minutes later Anna returns, unsuccessful. For safety’s sake, I need to get the generator going, so Foday and I make our way cautiously through the dark to the undressing tent, sidestepping furniture and trash scattered by patients. Tripping in the dark could expose us to Ebola, and neither of us is keen to be the next patient in Kailahun. In the undressing tent, the undressers shine flashlights so we can see to remove our gear. Unencumbered by my spacesuit, I race across the street to the generator room and succeed in restarting the generator, restoring power to most of the site. Other staff will enter High Risk to relocate patients from the unlit tents so medics can care for them.

December 12, 2014

Another hot, sunny day and I return to High Risk with my handyman for routine maintenance. As we hammer nails into an overhead beam, Andy – a British nurse with a thick northern accent – comes over and speaks through his spacesuit: “Hey mate, have you got a lot of this work to do?”

“No, just a few more nails and we should be done. If the noise is making any trouble for the medical work, we can stop.”

“No, no,” Andy says. “It's just that we've got this little girl dying and we're trying to give her a bit of peace in her last moments, but it's fine if you've just got a few more nails to finish.”

Looking over his shoulder, I see the girl lying on a bed outside a tent, her head tilted to one side, her little body unable to cope with the disease. Three medics in yellow spacesuits sit on the edges of her bed, stroking her head softly as if she were their own daughter. Adult fingers in a white surgical glove gently hold her small brown hand. It’s all they can do for her as she drifts away. Later, in the medical tent, I see the grave-stick prepared for her: Augusta*, age 2, patient number 1166. Andy has drawn a little flower on the grave-stick, next to her name. Five red petals on a simple stem, with two green leaves.

Late December 2014

Despite the tragedy, there’s good news at the centre almost every day: patients are discharged, families are reunited, and the number of patients steadily decreases. When I arrived in Kailahun, the centre was packed. Six weeks later, only two patients remain.

At the Vancouver airport, a quarantine officer takes less than an hour to check me over, while a border services officer stands guard. I’m given a thermometer, instructed to report daily to the government by phone, then I collect my luggage and step out into the chilly winter air. Looking right and left of the door, there isn’t a bucket of chlorinated water in sight.

*Name changed to protect patient confidentiality

Chris Anderson is currently working as a logistician with the Red Cross, helping combat Ebola in Guinea. Find out more or follow Chris Anderson at:

twitter: @photodiarist

web: photodiarist.com