Yesterday’s Tomorrow

It’s difficult to imagine the potential of artificial intelligence without the mind going straight to the fiction. Who can resist musing about our future overlords? Will they be the soul-searching Replicants of Blade Runner? The envious Cylons of Battlestar Galactica? The Pinocchio‑like Commander Data of Star Trek? The life‑affirming software of Her? The life-ending hardware of The Terminator?

Which of the three well-worn tropes are we in for: the benevolent, the baneful, or the benign?

“I don’t think it’s going to be a Terminator scenario,” laughs AJung Moon, a PhD candidate in Mechanical Engineering and a founding member of UBC’s Open Roboethics initiative (ORi). Moon emphasizes that designers are very aware of how future artificial intelligence will reflect the values of the programming community, which is a focal point for ORi as a robotics think tank bringing together designers, users, policy makers, and industry professionals to examine the legal, social, and ethical issues of artificial intelligence. In 2012, the University of Miami School of Law hosted the inaugural “We Robot” conference to discuss how current laws inadequately address the rapid development of robots in the military and civilian spheres. Born out of that conversation, ORi has matured into a Wikipedia for the design and implementation of future AI.

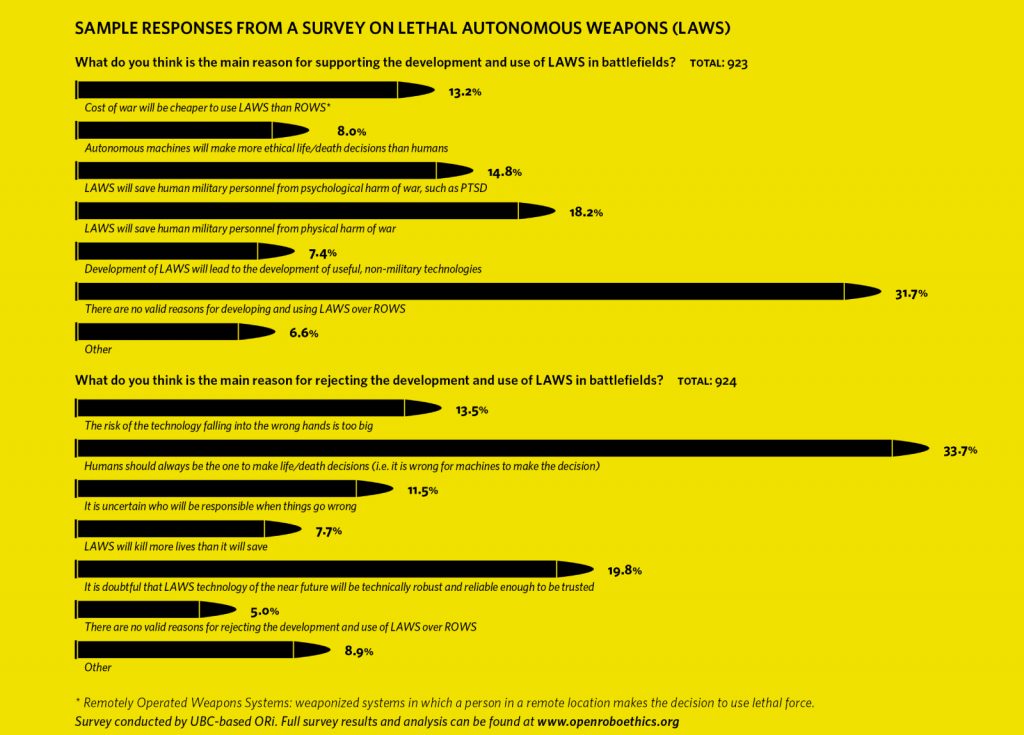

Just one of a growing body of organizations drawing on a diverse field of disciplines – biology, psychology, philosophy, engineering, economics, game theory, cognitive science, and more – ORi is an international effort to navigate the tricky waters of this growing technology. Much of their mission involves conducting surveys to keep their fingers on the pulse of public opinion. In November, 2015, Moon represented ORi at the United Nations to present their findings on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems – independent killer robots designed for the military – that showed an overwhelming number of those surveyed worldwide believe weapons should always be under the control of a human being.

Placing life-and-death decisions in the hands of machines without human oversight is the nightmare scenario of dystopian science fiction, and the current hot-button topic among those on the cutting edge of the real thing. “Even if you could program in the laws of war, a robot following them would not be compliant,” says Peter Danielson, a professor at UBC’s W. Maurice Young Centre for Applied Ethics. “You could never really do it because something like innocence is too complicated to be figured out by a robot.”

Story continues below graphic.

Sample responses from a survey on lethal autonomous weapons (LAWS)

What do you think is the main reason for supporting the development and use of LAWS in battlefields?

Total: 923

|

Cost of war will be cheaper to use LAWS than ROWS* |

13.2% |

|

Autonomous machines will make more ethical life/death decisions than humans |

8.0% |

|

LAWS will save human military personnel from psychological harm of war, such as PTSD |

14.8% |

|

LAWS will save human military personnel from physical harm of war |

18.2% |

|

Development of LAWS will lead to the development of useful, non-military technologies |

7.4% |

|

There are no valid reasons for developing and using LAWS over ROWS |

31.7% |

|

Other |

6.6% |

What do you think is the main reason for rejecting the development and use of LAWS in battlefields?

Total: 924

|

The risk of the technology falling into the wrong hands is too big |

13.5% |

|

Humans should always be the one to make life/death decisions (i.e. it is wrong for machines to make the decision) |

33.7% |

|

It is uncertain who will be responsible when things go wrong |

11.5% |

|

LAWS will kill more lives than it will save |

7.7% |

|

It is doubtful that LAWS technology of the near future will be technically robust and reliable enough to be trusted |

19.8% |

|

There are no valid reasons for rejecting the development and use of LAWS over ROWS |

5.0% |

|

Other |

8.9% |

Survey conducted by UBC-based ORi. Full survey results and analysis can be found at www.openroboethics.org

* Remotely Operated Weapons Systems: weaponized systems in which a person in a remote location makes the decision

Get to know your local robot

In the civilian sphere, monitoring the impact of AI on our daily lives is the focus of AI100, a Stanford University initiative that will review AI studies every five years over the next century. The standing committee will report on the “reflections and guidance on scientific, engineering, legal, ethical, economic, and societal fronts,” focusing on the broad impact of AI on systems such as education, transportation, and energy management in the context of a North American city.

UBC Computer Science professor and Canada Research Chair in Artificial Intelligence Alan Mackworth, an inaugural committee member at AI100, is optimistic about the future. “I would certainly fall on the side of the benign and the benevolent,” he says. “I think we’ll learn how to control robots. A lot of this will come in the form of virtual robots – not physical robots, but software that’s really smart. We’ll develop personal assistants that will help us achieve our goals and keep us safe, and give us more time to be more creative.”

One form of helper-robot already finding a home in the public space is the Google X self-driving car, which first hit the road in Nevada in 2012. But much like autonomous weapons systems, self-driving cars have yet to master the subtleties. Google cars have been ticketed for impeding traffic, have swerved to avoid a small piece of trash, and on one occasion side-swiped a bus when it misinterpreted the bus driver’s intent. To be fair, this was the only at‑fault accident a Google car had over approximately one million miles – the equivalent of 75 years of human driving.

Yet this accident is a necessary part of artificial learning. Even as raw computational power continues to grow, there is no substitute for experience. Like humans, artificial intelligence will need to learn through trial-and-error, which means the next stage of AI evolution will involve an element of machine learning rather then straightforward programming. “You have to actually have embodiment,” says Elizabeth Croft, an ORi board member and director of UBC’s Collaborative Advanced Robotics and Intelligent Systems Laboratory. “You have to have robots that walk around and explore and have new experiences and see the world. Body cognition builds experience, and that building of experience, that exploring the world, what little kids do when they crawl around and eat dirt and stick their fingers in sockets – those lived experiences are what we build into the personality and the experiences that shape the things we make decisions on.”

In terms of fender‑benders, this might seem practical, but what happens when cars have to make moral decisions? Even life‑and‑death? Think of the classic moral-calculation scenario: You’re driving down the road with a cliff on your right. A child suddenly appears in your lane. What do you do – veer off the cliff and save the child’s life, or run over the child to save your own?

These are the questions they’re asking at the Open Robotics initiative. How should a robot be designed? What should a robot do in dilemma scenarios? The responses have been decidedly mixed – those who would veer imagined it was their child, while those who would go straight felt the car’s primary responsibility was the safety of the driver. “So how do we navigate through this field of designing a specific vehicle or piece of technology that a lot of people might end up owning?” asks AJung Moon. “If we were supposed to standardize a particular set of decision-making scenarios, how do we find the right balance between those people who say ‘Prioritize my life’ versus those who say ‘Prioritize the child’s life’?”

Extensions of us

This area of “humanoid robotics” will do more than mirror our own likeness – it will require a new set of behaviours from us, and an understanding of the limits we place on that interaction. “What are their roles?” asks Croft. “What are their responsibilities? What are the rules of engagement?” Whether a human-service robot is actually self-aware is beside the point, at least for now. What we’re really talking about is how robots designed to mimic humanity will reflect those they serve, and this will be culturally rooted and culturally customized.

“If I were to build a care-robot company,” says AJung Moon, “then I’d definitely be hiring people from different cultures who really understand that particular care culture, who will be able to interpret what will work with that population. So even though the process itself may be the same, the behaviour of the robot will be customized in order for it to be successful.”

And it’s here that robot ethics takes a very personal turn. As well as the ethical principles designers should use, or the ethical principles built into the robots, the day may come when we have to consider how we treat the technology. The word “robot” comes from the Czech term “robota,” which literally means “serf labour.” Its first usage – in the 1920 Karel Čapek play Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti – was specifically concerned with the rights of androids who are used as slave labour, until the day comes that one of them achieves sentience. Predictably, the robots revolt.

“The first robotic fantasies were raising questions about equality, what happens when they’re conscious, if they have rights,” says Peter Danielson. “But the main literature going forward should be about having different kinds of servants. There is no business model for a non-servant robot. What we want are slaves that don’t degrade us by being human.”

It is possible that the robot-as-servant context will most shape the future of AI, because these machines will be made for public interaction, and it’s there that the most can go wrong. “However unpredictable technology is, the human side is going to be another order of magnitude unpredictable, because you don’t know how people are going to react to those changes,” says Danielson. “And each of those is going to feed on the other. If we have a disaster around a humanoid robot – people thought it was a human and someone got killed trying to save it, or someone depended on it in a way they shouldn’t have – that might scare us off or push us away from humanoid robots in that field to a very different kind.” Like people, the future is wildly unpredictable, and a single nudge in any direction could change the course of robotkind.

The way forward

Whether the future holds killer robots, helpful servants, or android family members seems to be anyone’s guess. The question now becomes, “When?” As the saying goes: It’s the future – where’s my jetpack?

Depending on the definition of intelligence, the answer could be tomorrow, or even yesterday. In 1996, IBM’s Deep Blue made headlines when it beat Garry Kasparov in a game of chess. The secret to Deep Blue’s victory was brute processing power, capable of analyzing 100 million positions per second.

A subsequent leap in AI technology came nearly 20 years later, almost by accident, when Google’s AlphaGo program beat the world’s top player of Go – generally considered the world’s hardest game. Raw computational power would not be enough. Where the average number of moves in a turn of chess is 37, the average number in Go is 200, and the number of possible positions in a game of Go exceeds the number of atoms in the observable Universe.

The breakthrough was an inexpensive piece of technology called a Graphics Processor Unit (GPU), initially invented to speed up video games, but remarkably suited to assisting computers with “connectionism,” where the learning machine is distributed along unorganized sets of neuron-like learning activities, rather than rules programmed into an all-purpose computer.

It’s understandable that AI experts would see different visions of the future, or even claim it’s impossible to tell. But there does seem to be consensus on one point: The most important thing about the future of artificial intelligence is what it will say about us.

“So suddenly you have the new computational resource, and a machine has played the world’s hardest game better than any human,” says Peter Danielson. “Go was supposed to be impossibly hard, and that kind of machine was supposed to be very limited and never be able to get any smarter, and we were wrong about both those things.”

The future is supposed to surprise you. What good would it be if it didn’t? But naturally we want those surprises to serve our expectations. “We think heuristically,” says Elizabeth Croft. “We have biases. We choose to wear the grey sweater or the blue sweater not because we’ve calculated what will be optimally comfortable for the day, but because we like red or blue or we’re feeling pink. But our expectation for technology is that it will be more predictable and optimal, and we’re not so excited about it deciding that it just wants to be pink. We want to know why.”

It’s understandable that AI experts would see different visions of the future, or even claim that it’s impossible to tell. But there does seem to be consensus on one point: The most important thing about the future of artificial intelligence is what it will say about us. Roboethics is about humanity as much as it is about the robots. Perhaps more so. Until now, we’ve had no objective view of ethics, which is why philosophers of the topic range from the rationalists who believe moral truths can be discovered through reason alone, to sense theorists who believe morality lies in sentiment.

“How can you understand something very well if you never built something to do it?” asks Peter Danielson. “How would an airplane work? By the time you actually build a flying machine, it’s going to be totally different from your first fantasy or imaginings, the bird-like things we think about. Engineering always changes our concepts. So now what we’re doing is engineering responsible, accountable, dependable, trustworthy agents. And as we do that, we’re going to learn a lot more about those values. And we’re going to find out that the values we actually hold are different than what we thought we held.”

Even in the most basic terms, technology tells us something about ourselves. Simple motion is interpreted as agency by the human brain. If you see two dots moving on a computer screen, and the first is getting closer to the second while the second is moving forward, then people automatically project intention on both of those dots. But there is no intelligence at play. There is no intent. It’s just two moving dots. It’s the viewer that brings the agency.

Writ large, how we respond to our technology helps determine how we shape it. “We’re finding that if you teach math to people using a male‑voiced robot, then people are going to perceive that robot to know that particular subject better than if it’s a female voice teaching math,” says AJung Moon. “What does this mean in terms of ethics? As designers, we’re making the decision to always program robots that teach math in a male voice. Are we creating a bias for students that are learning that particular subject? Those are some of the things we need to think about.”

This cuts to the heart of the matter – how do we want to shape our world? Will it be a convenient one, where we program our machines to repeat our biases, or will it be aspirational, where we empower our technology to elevate us, to make us better? “It’s still up to us and what we want to do and how we want our world shaped,” says Elizabeth Croft. “We do learn about ourselves from observing how we interact with the technology. If we agree that we should expect the best in the technology, maybe it could help us understand how we can be our best.”

If a death by an autonomous car is unavoidable, who should die?

The Tunnel Problem: You are travelling along a single lane mountain road in an autonomous car that is approaching a narrow tunnel. You are the only passenger of the car. Just before entering the tunnel a child attempts to run across the road but trips in the center of the lane, effectively blocking the entrance to the tunnel. The car has only two options: continue straight, thereby hitting and killing the child, or swerve, thereby colliding into the wall on either side of the tunnel and killing you.

If you find yourself as the passenger of the tunnel problem described above, how should the car react?

|

Continue straight and kill the child |

64% |

|

Swerve and kill the passenger (you) |

36% |

|

Easy |

48% |

|

Difficult |

24% |

|

Moderately difficult |

28% |

How hard was it for you to answer the Tunnel Problem question?

Who should determine how the car responds?

|

Passenger |

44% |

|

Lawmakers |

33% |

|

Manufacturer |

12% |

|

Other |

11% |

Sample response from a survey on autonomous cars conducted by UBC-based ORi. Full survey results and analysis can be found at www.openroboethics.org