North by Northwest

There is a word in North Korea: Juche. Loosely translated as “self-reliance,” juche has served as a central pillar of North Korean foreign policy since the country retreated from the global community nearly 70 years ago. More than a patriotic code word, juche is a guiding principle of the country’s national identity, and, for most of us in the West, it’s one of the few things we actually know about the famously closed society.

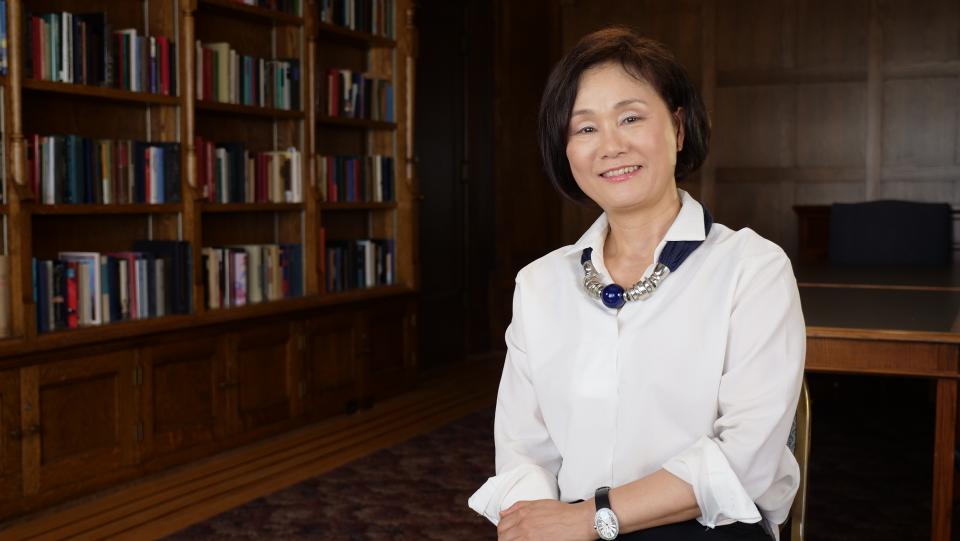

But being self-reliant doesn’t mean losing one’s curiosity about the rest of the world, and, thanks to Professor Kyung-Ae Park at the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, UBC has been granted a rare window into life in this reclusive state. For more than 20 years, Park has been carefully navigating the complexities of Asian-Canadian affairs, bypassing the maze of political entanglements to establish relationships – and eventually collaboration – between scholars in Canada and North Korea (officially the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or DPRK).

In 2010, she created the Canada-DPRK Knowledge Partnership Program (KPP), a unique scholarly enterprise designed to facilitate academic exchanges between UBC and six North Korean universities. Founded on the belief that sharing knowledge is necessary for building human capacity, the KPP has cautiously avoided the peaks and ditches that litter the political landscape, serving as an unofficial ambassador between our two countries by using what’s known as a “Track II” approach to international relations, an unofficial channel that becomes handy when Track I (government) has gone off the rails.

“Since 2011, we’ve been hosting North Korean professors at UBC every year, which means we were able to do it every year regardless of the political situation,” says Park. “I don’t have any political agenda. But I have a strong belief that access to education, access to knowledge, is a universal human right. So I was just trying to provide such access for North Korean scholars, and was hoping to improve bilateral relations through these scholarly exchanges.”

“I have a strong belief that access to education, access to knowledge, is a universal human right.”

~ Kyung-Ae Park

Perhaps one of the keys to KPP’s success is its clarity of purpose. Focused exclusively on the areas of economics, finance, trade, and business, the KPP hosts six North Korean scholars at UBC every year for a period of six months. Arriving in early July, the scholars use the summer to study English, then spend the fall semester alongside undergraduate and graduate students in courses focused on international trade, finance, economics, and management. The visitors then use what they learned at UBC to create a group research project, which they take back to the DPRK and present to their academic peers.

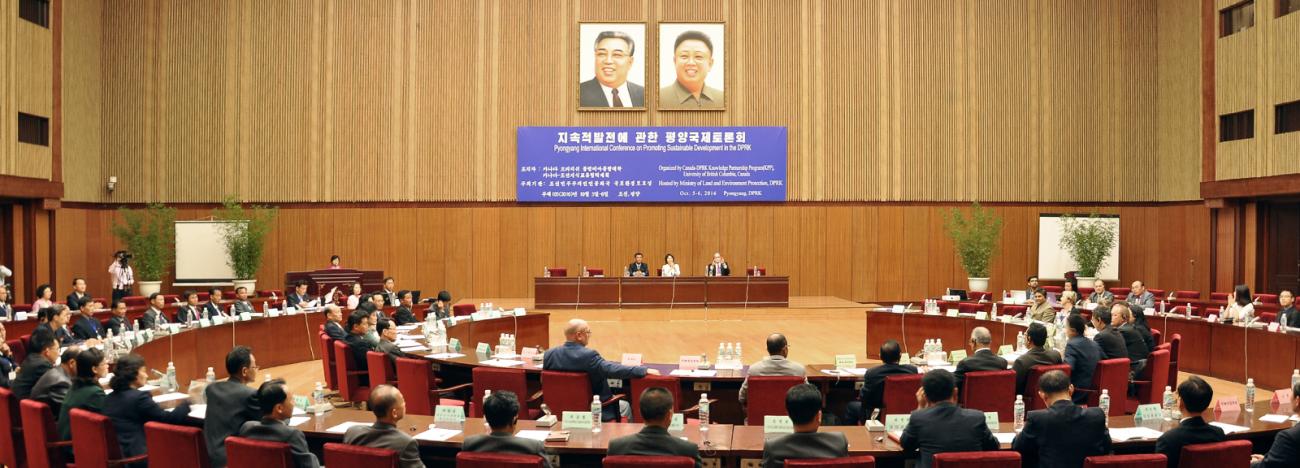

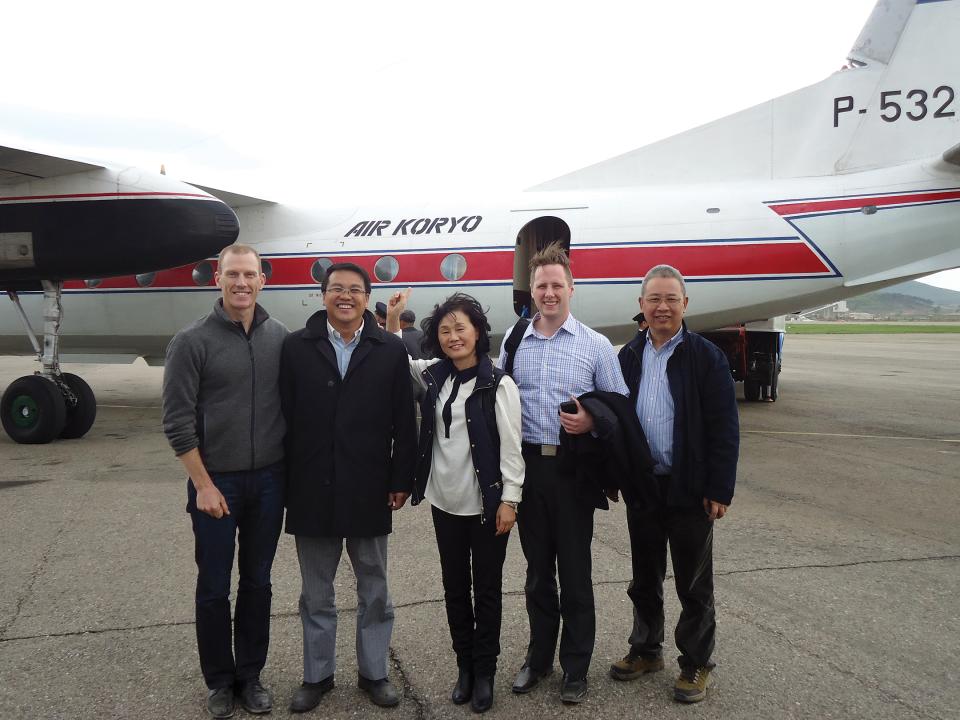

Augmenting the visiting professor program are occasional KPP conferences in North Korea, where Park organizes seminars and workshops between the DPRK and foreign scholars. The first two of these conferences in 2013 and 2014 focused on special economic zones in North Korea, bringing together more than 20 foreign experts and nearly 200 domestic scholars and government officials. In addition, KPP organizes study tours abroad for North Korean experts, providing them with opportunities to interact with foreign scholars outside of their country and gain practical, hands-on experience.

Although the KPP officially launched in 2011, the idea of an academic exchange between the two countries first took root in Park’s mind in the 1990s. After earning her political science degree from Yonsei University in South Korea, and her PhD at the University of Georgia in the United States – where she focused on political development in China and North Korea – Park arrived at UBC in 1993, just as Canada was beginning to engage North Korea on the potential for normalized relations.

From 1995 to 2000, Park made several visits to North Korea and hosted seminars for a North Korea delegation at UBC, all stones along the path to establishing official diplomatic relations between the two countries in 2001. But the honeymoon was short-lived. In January 2002, US President George W. Bush declared North Korea an “axis of evil,” rejecting the “sunshine policy” negotiated by the previous administration and South Korea and severely straining the DPRK’s relationship with the West. By the end of the year, concerns over North Korea’s weapons program led to US sanctions against the country, and Canada was frozen out along with the rest of the West.

“From 2001 on, there was not much interaction at all between North Korea and Canada compared to the latter part of the 1990s,” says Park. “So I thought we might want to consider interactions in the non-political arena – academic exchanges, knowledge-sharing programs, scholarly exchanges, those sorts of non-political activities.”

After much consideration and careful negotiation, Park proposed the KPP to North Korea in 2010. A year later, the first six scholars arrived in Vancouver, establishing UBC as a pioneer in academic relations with North Korea.

As the centerpiece of the KPP, the visiting professor program has proved beneficial for both countries, offering surprises to UBC faculty as well as the DPRK scholars. “Given how much we hear about North Korea and how little we know, those interactions allowed me to learn quite a few things,” says Yves Tiberghien, who met with the visitors while he was director of the Institute of Asian Research from 2012 to 2017. “In conversations, the scholars were quite humorous. They were lively, quite blunt, and we had good discussions. I gave one group a list of guest lecture topics about the economy, and the first thing they picked was Chinese economic reforms. For me it was edifying to discover that there is an amount of tension and misunderstanding between North Korea and China – often in the West we don’t realize. So it would take this Canadian scholar to talk about the economy of China to them.”

As enlightening as it is for UBC faculty and students to work side‑by-side with people who have never before left their home country, it is positively eye-opening for the visitors themselves.

As enlightening as it is for UBC faculty and students to work side-by-side with people who have never before left their home country, it is positively eye-opening for the visitors themselves. “They take tons of pictures – they go around and look at things with fresh eyes,” says Zorana Svedic, a lecturer at the Sauder School of Business who serves as this year’s academic advisor to the visiting scholars. “It’s kind of nice to see them really enjoying their time and trying to absorb as much as possible. It’s very unusual to see people who have never stepped out of their country before, so it’s a big culture shock for them because they’re just not used to talking to people from different cultures, different races, different languages.

“I come originally from Serbia,” she adds, “which is a very Caucasian society – there’s not many races of any other kind. And I grew up in Communism, so I kind of understand some of the things they have to deal with. But still, we were never as closed as North Korea is, so I haven’t come close to experiencing the things they’ve experienced.”

Besides their UBC activities, the DPRK scholars take a field trip to Toronto during their stay, where they meet with UT professors and corporate CEOs and get a taste of Eastern Canada. But as valuable as this ancillary cultural interaction is, the focus of the program is strictly academic, and a large part of that is an attention to pedagogy.

The visiting scholars don’t just absorb knowledge, they absorb the manner in which it’s distributed – how students choose their courses, how professors execute their presentations, and how teachers and students interact in the classroom. DPRK universities tend to follow the “sage on the stage” model: the professors lecture and the students take notes. Western education, particularly business schools, are more inclined to participatory models in which students cooperate in working groups and collaborate with their professors.

“My courses are very interactive,” says Svedic. “People work in teams and students ask a lot of questions. Especially in the Sauder School of Business, we really encourage participation – that’s one of our goals, for students to participate and collaborate with each other. That’s very new to [the North Koreans], so it’s interesting for them to learn about this approach. Our whole goal is for them to try to absorb some of the teaching practices that we have here and take them home [to] utilize in their own classes, [to] spread this knowledge, spread this teaching style across their colleagues as well.”

This is one reason why these scholars are selected for the program earlier in their careers, usually younger professors who can return to their home universities and apply an interactive pedagogical strategy in their own classrooms, passing on not just knowledge, but a new way of learning.

“If we have a chance to work with North Korea in the future, the human capital will be these people.”

~ Yves Tiberghien

Naturally, the KPP has earned some notice from other institutions. “It’s praised all around,” says Tiberghien, who has heard glowing reviews of the program at conferences in Japan, South Korea, and the US. “The cadre of Korean scholars that have come to UBC is pretty much the only group that has gained some factual knowledge about the economy outside of North Korea, so the program is held in high regard by a lot of people that I hold in high regard. If we have a chance to work with North Korea in the future, the human capital will be these people.”

Alumni of the program are already having a substantial impact in North Korean classrooms. “Professors have been devising new courses based on the knowledge they garnered at UBC, writing new textbooks and research books, and sometimes translating books they brought from Canada into Korean and sharing them with other universities in the DPRK,” Park says.

But exchanges between nations don’t happen in a vacuum – conversations about economics and international trade must take into account the global economy, which means bringing other countries into the mix. In 2015, the KPP organized scholars from Kim Il Sung University and the University of National Economy, as well as a number of government officials, for a study tour of Indonesia. They researched economic management issues and Jakarta’s development strategies in an unprecedented dialogue with Indonesian scholars and administrators. Later in the year, the KPP worked with the United Nations Institute for Training and Research to bring 12 North Korean scholars and officials to Switzerland to study the country’s agricultural practices.

So far, the program has largely stuck to its original intent, focusing on economics, business, trade, and finance. But in October 2016, Park broke new ground when she organized a conference in Pyongyang on the issue of sustainable development. Tapping 130 North Korean experts and 16 foreign scholars, the conference covered climate change adaptation, sustainable agriculture and tourism, and forest, water, and waste management. The conference was followed in 2017 by two sustainable development workshops in Pyongyang and Mt. Paektu, organized by the KPP and co-hosted by the DPRK Ministry of Land and Environment Protection and the Ministry of External Economic Affairs.

As impressive as the program is, and as successful as it’s been, the spectre of international politics always looms in the distance. Relationships between the DPRK and Western countries has lately reached a fever pitch, potentially threatening any small enterprise trying to make a positive difference.

But if simmering tensions between the DPRK and other countries do cool down and diplomatic relations are normalized, the KPP will likely help lead North Korea into a greater role in the global economy. “We’re not doing any political teaching,” adds Svedic. “We’re teaching business. If North Korea is to open towards any kind of international trading or international business deals, they need to be more familiar with the business practices outside of North Korea.”

“At this moment, when there is so much rattling of the sabres and so much competition and talk of war,” adds Tiberghien, “to have a peaceful program targeting economic issues as a chance for discussion with top scholars in North Korea is very valuable. It gives some hope for another way.”

Professor Park holds the Korea Foundation Chair in UBC’s School of Public Policy and Global Affairs.